I Hope This Year "Black Woodstock" Gets Its Own Name

by Eli James

I Hope This Year "Black Woodstock" Gets Its Own Name

A memory by Eli James

A documentary about a mostly forgotten 1969 music festival known as “Black Woodstock” is currently in production. Its director is Roots co-founder, drummer and cultural encyclopedia Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson. In a statement last December, Thompson said, “I was stunned when I saw the lost footage for the first time. It’s incredible to look at 50 years of history that’s never been told, and I’m eager and humbled to tell that story.”

Eager and humbled was pretty much how I felt when I first heard of the existence of a “Black Woodstock.” It was the summer of 2019, about five months before the documentary was announced, about seven months before the coronavirus put a screeching a halt to live entertainment and some forms of joy. I was killing time on a bench outside a coffee shop in Brooklyn before heading off to attend a support group for people who like to heap shame upon themselves. I was an unemployed actor and writer, was getting down to my last few bucks, and was hoping the internet would grant me a burst of joy that would get me through the next few hours. I was specifically looking for ways to make no-cost memories via New York’s Summerstage calendar, an annual program of free outdoor concerts that runs spring through early fall across the five boroughs of New York City. I might not be able to afford tickets to the Wu-Tang reunion show, or “Hamilton,” or things like … dinner … but surely there was a free concert my girlfriend and I could go to that would be cooler than all of that.

As I scrolled through the Summerstage listings on my phone, jotting down concerts of passing interest, I did what must have been a discernible double-take when I saw an event with the heading “Black Woodstock 50th Anniversary.” What? There was a Black Woodstock? In 1969? The same year as … Woodstock Woodstock?

I clicked on the event link. The description read, “This concert celebrates the 50th-year anniversary of the Harlem Cultural Festival. Taking place in the summer of 1969, the original festival held a series of concerts in Mount Morris Park (now known as Marcus Garvey Park), to celebrate Black pride, empowerment, music, and culture, and featured the likes of Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, B.B. King, Sly & the Family Stone, Jesse Jackson, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Mahalia Jackson, and others.” The ad featured a picture of rapper Talib Kweli, one of the stars of the conscious rap renaissance that bubbled out of New York in the late ‘90s. He was to be the show’s co-host and headlining act.

I was in shock. I was still blinking, eyebrows in scrunch mode. How had I never heard of this 50-year-old concert made up of all these legendary performers — Stevie, Nina, Sly, Gladys! — in my own city? I was gripped by equal parts excitement, disbelief and indignation. The latter came from thinking I was well-versed in the many 50th anniversaries the year 2019 would be honor-bound to celebrate. I prided myself on having a better working knowledge than most people my age of the momentously good and momentously bad stuff that happened or started in 1969: Sesame Street, Abbey Road, Woodstock, Altamont, Nixon’s first term, the debut of Monty Python, the moon landing, Stonewall. And I really thought I knew about the musical touchstones of the ‘60s, since I’d spent every year since 10th grade reading about them, listening to them, memorizing their names. I’d been a Beatles nerd, a Bob Dylan nut, and a Motown kook for decades now. This e-flyer showed me that I didn’t know it all, and had me wondering where my priorities had been for the last twenty years of idealizing the ‘60s music scene.

Survival of the Whitest

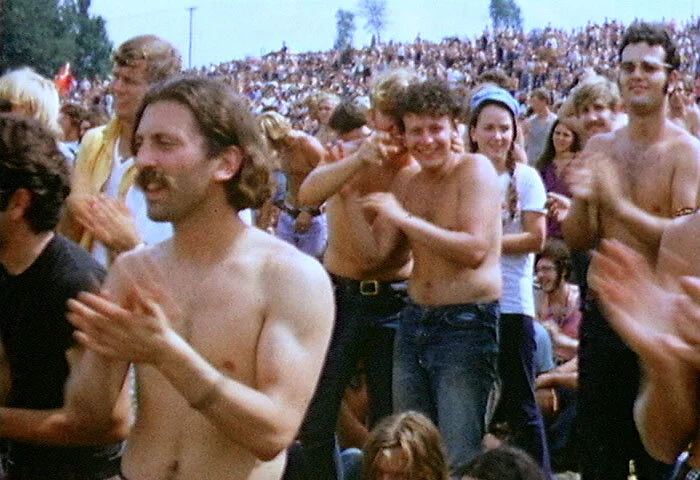

The music festivals of the late ‘60s that achieved “legendary” status and are remembered generations later — like the Monterey Pop Festival, Altamont and Woodstock (pictured) — are the ones that attracted majority-white audiences and featured mostly white performers. Their places in history were helped by the wide release of feature-length documentaries, which the Harlem Cultural Festival didn’t get.

After digging into the festival’s history, I realized that if I was ignorant about Black Woodstock, then so was pretty much everyone. My illiteracy on the subject put me in some fairly elite company. Questlove, an artist who in every interview he gives demonstrates a Ph.D.-worthy knowledge of music history, admitted his shock when he saw the footage for the first time. The remnants of the festival must’ve been buried pretty deep if he was just learning about it. When I began my search for intel on the original festival (a search I’ve now spent a year on), the first article that popped up was a feature-length history in Rolling Stone titled, “This 1969 Music Fest Has Been Called ‘Black Woodstock.’ Why Doesn’t Anyone Remember?” Okay. Maybe I could let myself off the hook for not knowing something a lot of people didn’t know, and just enjoy the learning.

In the week leading up to the anniversary show, I spent much of the time I probably should have been using to look for work to instead look for more info on the Harlem Cultural Festival. In his Rolling Stone article, writer Jonathan Bernstein offered a solid foundation on how the festival came to be, the social and political climate in New York leading up to it, and a compelling albeit unsettling portrait of the festival’s forward-thinking, enigmatic founder, Tony Lawrence. Lawrence, a St. Kitts-born pop singer and actor with some minor hits in the Caribbean and the U.S., found himself living in New York City in the mid-1960s, balancing his music and acting career with community organizing in his neighborhood of residence, Harlem. In 1967, he was hired by the New York City Parks Department to push forward his vision of a series of free concerts for the uptown area. Lawrence longed to do something to lift up and celebrate the predominantly Black neighborhood, which had been subject to a painful economic upheaval around this time, and was suffering from increasingly poor relations between police and residents. Lawrence convinced Mayor John Lindsay, a recently elected Republican who was eager to build bridges with Black New Yorkers, to fund a six-week outdoor celebration in Harlem. Lindsay’s newly appointed parks commissioner, August Heckscher II, also gave the operation his full support — and the first Harlem Cultural Festival opened in the summer of 1967 at the corner of 129th Street and 7th Avenue. Jazz legend Count Basie, gospel star Mahalia Jackson and powerhouse R&B singer Bobby “Blue” Bland were among the entertainers that summer.

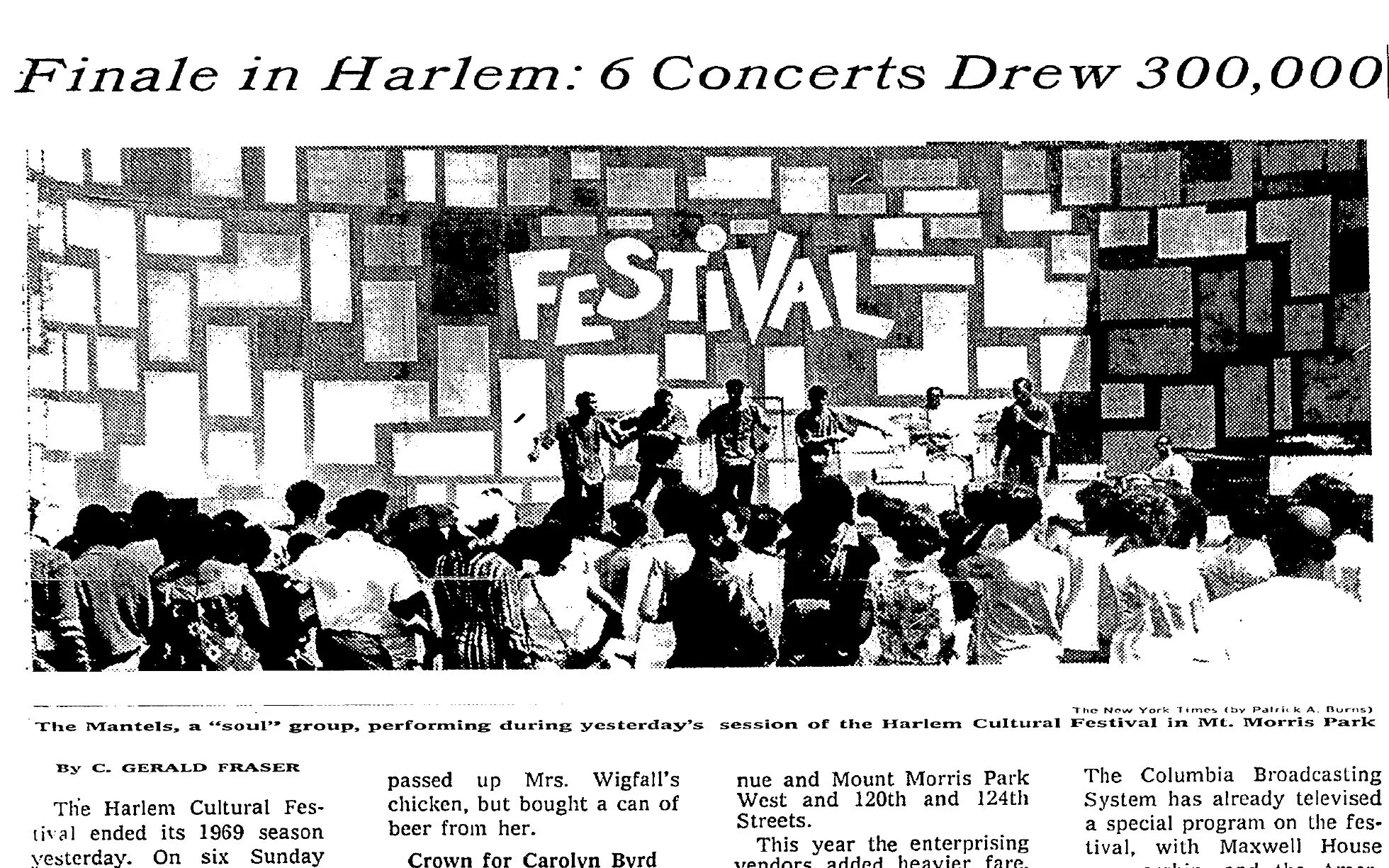

In 1968, Lawrence and Heckscher moved the festival a few blocks southeast to the more spacious Mount Morris Park, at 124th Street near Madison Avenue. Approximately 25,000 people turned out each night to take in performances by sax player King Curtis, soul singer Joe Tex, not to mention gospel groups, Latin bands and the LaRocque Bey Dancers, whose school for African dance in Harlem is the oldest in the country. The success of the ‘67 and ‘68 Harlem Cultural Festivals helped Tony Lawrence grow out his vision of a star-studded cavalcade for 1969, one that would feature the top entertainers in the country. Hal Tulchin, a veteran television cameraman, put together a team to capture what was sure to be a historic six weeks of music and celebration. D.A. Pennebaker’s 1967 film of the Monterey Pop Festival had set a new blueprint for what a great concert film could do for the culture. Besides capturing mesmerizing performances with his avant-garde cinematic eye, Pennebaker’s documentary helped launch the U.S. careers of The Who, Jimi Hendrix, Ravi Shankar and Janis Joplin.

------

The Harlem Cultural Festival of 1969, also known as “Black Woodstock,” ran June through August that year, and featured an all-star lineup of Black entertainers, including Gladys Knight and the Pips (pictured), Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, B.B. King and Sly and the Family Stone. They played to a mostly Black audience that numbered in the hundreds of thousands in Harlem’s Mount Morris Park, while the Woodstock Festival took place 100 miles north.

Soon after I saw the ad for the Black Woodstock anniversary show, I contemplated how not-Black the more famous Woodstock had been. I’d had an image in my mind of those three-and-a-half days at Yasgur’s Farm as a great rainbow-colored coming together of bands, fans and counterculture warriors. Surely every background had been represented there. Wasn’t that what the Woodstock generation was all about? After a moment of visualizing scenes from Michael Wadleigh’s classic “Woodstock” documentary, I realized this was a fantasy I had been wishfully holding on to. On that bench where I discovered “Black Woodstock,” I balled up my palm to start counting, just off the top of my head, the number of performers of color who’d played at the upstate Woodstock. Ritchie Havens, Jimi Hendrix, Santana, Sly and the Family Stone…

My finger-tally made use of only one hand, and didn’t even get to a full five fingers. Out of the dozens of acts who played that weekend, were there only four that weren’t fronted by a white person? There had to be more than that, I thought. But maybe there weren’t. Had the producers of Woodstock invited more Black artists than could actually make it? Had Stevie Wonder been invited to play? Or Nina Simone? Or was Woodstock, intentionally or not, a concert that fulfilled a predominantly white vision of American counterculture? It doesn’t strain plausibility to think that, in 1969, it was more than restaurants, workplaces and neighborhoods that were segregated along racial lines. It stands to reason that white and Black music, and their accompanying youth rebellions, were also operating on different sides of a fence, even amidst calls for change. I Googled images of the crowds at Woodstock, scanning through some of the more famous stills. A sea of white faces and bodies was all I could see. The pictures taken at the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival tell the opposite story. There are no non-Black faces to be found in the Harlem park that summer. There’s one if you count Mayor Lindsay, who was campaigning for re-election that year.

It’s unclear who first coined the term “Black Woodstock,” but Hal Tulchin, the festival’s videographer, certainly used the descriptor to entice TV networks to lease his footage, and to convince would-be producers to turn his more than 40 hours of high-definition color video into a feature-length film. Tulchin’s work ultimately failed to get wide distribution, though excerpts of it did see airtime in the form of two TV specials on local New York stations in the last half of 1969. Some of his video was used in two posthumous Nina Simone releases — one an enhanced CD/DVD issued in 2005 called “The Soul of Nina Simone,” the other the 2015 Netflix documentary “What Happened, Miss Simone?” With the exception of a few other leaked clips on the web, most of Tulchin’s “Black Woodstock” footage has never been seen. The powerful excerpts featured in “What Happened, Miss Simone?” prompted the few who knew of the Harlem Cultural Festival to seek out Tulchin to work on assembling a documentary. Tulchin allowed his footage to be digitized and restored by the archiving company Historic Films, whose president, Joe Lauro, enlisted a pair of filmmakers to work with Tulchin on a feature. But the deal “unraveled over financial issues,” according to The New York Times, and Tulchin sat on the boxes of videotape until he died in 2017.

The failure to get full release of the footage was undeniably linked to racial divisions. As much as it wanted to attract people from all over, the Harlem Cultural Festival was a local event for just one part of a city, a part that was Black. Years later, when describing the barebones camera and sound crew he used to shoot the festival, Tulchin said, “It was a peanuts operation, because nobody really cared about Black shows.”

Of all the factors leading to the disappearance of Black Woodstock from the public consciousness, this may be the linchpin. The festival might very well be known by its own name, without the injustice of a comparative label, if only a documentary had come out years ago. We might be saying “Harlem Cultural Festival” in the same breath as “Monterey Pop Festival” or “the Beatles at Shea Stadium.” A documentary that carefully weaves together a moment of forgotten art can turn an entire generation on to what was thought to be a niche interest. This was the power of nonfiction music films like the Maysles brothers’ “Gimme Shelter,” Malik Bendjelloul’s “Searching for Sugar Man,” Jeff Levy-Hinte’s “Soul Power,” and D.A. Pennebaker’s other landmark documentary, “Depeche Mode 101” (that’s right, I said it). They take you there — the crushing lows and the transcendental highs, and the parts where the crew is setting up the P.A. system in the rain when all of a sudden the money runs out. It sticks with you. A documentary matters, and the Harlem Cultural Festival didn’t get one.

------

On June 18, 1969, Tony Lawrence staged a small-scale preview performance of the festival at Rockefeller Plaza in Midtown Manhattan, hoping to attract New Yorkers from other neighborhoods and backgrounds to Harlem that summer. According to a contemporary article in The New York Times, Olatunji, the famous Nigerian drummer, implored onlookers at Rockefeller to “come up to Harlem. Have no fear. You’ll see people with soul and love performing.” He and Lawrence hoped to reassure non-Harlem natives that it was okay to go uptown. This might be hard to conceive of in today’s New York, but for many white New Yorkers, going uptown was just something you didn’t do.

In New York City’s Black neighborhoods, the racial tension buoyed by generations of injustice was no less palpable than it was in the Jim Crow South; it just took a different form. Northern cities didn’t have the same number of explicitly racist laws as southern ones, but iniquities in housing, income, health care and policing were working overtime off the books. New York still felt the impacts of the 1964 “Harlem riots,” six days of July protests that morphed into violence on the third day. The demonstrations began after an an off-duty NYPD lieutenant shot and killed a 15-year-old Black teenager on the Upper East Side. Contemporary descriptions of the riots eerily resemble the ongoing reaction to the May 2020 killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers. Historical records capture the same level of outrage in the streets, the spread of demonstrations to cities across the country, the vocal anger over Black Americans’ treatment at the hands of white police officers and a white-run justice system, the bursts of violence and looting, the brutality of police crackdowns on protesters, and the reactions of politicians during that election year. Many lawmakers sidestepped having to address issues of systemic racism by calling for an immediate return to “law and order.” The 1964 riots occurred two weeks after the signing of the landmark federal Civil Rights Act in Washington.

In April of 1968, Harlem was one of many urban areas nationwide in which outrage over Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination spilled over into days of violence. Crime in New York City saw a huge uptick that year, spurred by economic decline, a skyrocketing debt and rampant police force corruption. Though Mayor Lindsay had pledged to bridge the gap between Black and white New Yorkers, and worked to roll out new progressive programs — Tony Lawrence introduced the white mayor during one of the festivals as “a soul brother downtown who is working hard for us” — the suffering of Black people at the hands of the NYPD went largely ignored. Allen Zerkin, who worked in Lindsay’s parks department in the late ‘60s, believed the mayor’s goodwill programs in majority-Black neighborhoods were motivated in part by a desire to tamp down the potential for riots. “The Lindsay administration was both dedicated to civil rights and also concerned about the risks of rioting,” he told Rolling Stone. “The Harlem Cultural Festival has to be seen in that context.”

In the summer of 1969, over a year after his death, Americans throughout the U.S. were still feeling the pain of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. That pain was particularly acute in majority-Black neighborhoods like Harlem, where injustice, neglect and an economic downturn caused widespread suffering.

Jamal Joseph, an activist and theater artist who had been active in the Harlem chapter of the Black Panther Party at the time, spoke at a panel discussion at Harlem’s Schomburg Center in the run-up to the 2019 anniversary show. He described to the audience “how bad things were in Harlem in ‘69. We’re talking about a Harlem Hospital that was known as ‘the butcher shop.’ You would see a trail of blood and know that it would lead to the hospital — because someone had been shot, because somebody had been beaten. You’re talking about a police force that was clearly an occupying army, that was mainly white, that would whip ass first and ask questions later. In fact, getting beat up by the cops was like a rite of passage for us.”

In April of 1969, Joseph became the youngest member of the “New York 21,” a group of Panther Party members in Harlem who were indicted on charges of conspiracy to set off bombs at police stations and at public spaces including the New York Botanical Garden, Macy’s and Wall Street. (Two years later, the New York 21 would be cleared of all 156 charges against them. Some of them had been facing sentences of up to 300 years.) Soon after their arrest, a celebrity-backed campaign was started to raise money for the Panthers’ defense and to boost awareness of what was seen as a trumped-up charge.

Such was the atmosphere when the Harlem Cultural Festival kicked off in Mount Morris Park on June 29, 1969. The NYPD refused to provide security for the performances, leaving members of the Black Panther Party and young men known as The Commanders to step in. The festival ran on six nonconsecutive Sundays through August 24. The Woodstock Music and Art Fair took place in Bethel, New York, the weekend of August 15.

-----

Existing video of the ‘69 Harlem Cultural Festival shows how much had been invested in it. Lawrence had managed to secure Maxwell House as a sponsor, and also got support from CBS and ABC. “The entertainers charged me top price,” he told a New York Times reporter at the time, “and we paid it.” The broad stage was awash in giant amplifiers, and the backdrop of multicolored panels was reminiscent of a “Laugh In” set, with “Brady Bunch”-style lettering spelling out “Festival.” A long runway ran through the center of the audience, allowing for added theatrics from the performers. Unlike the casually dressed audience members, who wore a minimum of loose garments to cope with the summer heat, the stars onstage were adorned in no small amount of skintight velour and buckskin fringe.

Sixty-thousand people turned out for the festival’s opening day. Audiences packed into the 20-acre park in front of the stage and spread out along the steep mica schist rock formations surrounding it. They watched Sly and the Family Stone rip into hits pulled from their chart-topping album “Stand!”, which had been released that spring and featured the now-evergreen radio staples “Dance to the Music,” “Everyday People” and “Sing a Simple Song.” They heard Nina Simone and her band perform “Four Women,” a moving portrait of four Black women that had been banned on some radio stations, after accusations from some that the song perpetuated Black stereotypes. And they listened as she premiered a brand-new composition called “To Be Young, Gifted and Black,” soon to be a civil rights movement anthem. Simone also performed her answer song to the Beatles' “Revolution,” written seemingly from the revolutionary’s perspective. Instead of standing back in judgment and demanding more details on the ultra-Left’s plans for the future, as John Lennon does on the original, Simone puts the total restructuring of society in the present tense, “Now we got a revolution, ‘cause I see the face of things to come. The constitution, my friend, it’s gonna have to bend.” And she blew all of these incendiary moments out of the water when she launched into a band-backed recitation of David Nelson’s poem “Are You Ready, Black People?”, which contains the lines, “Are you ready to smash white things, to burn buildings? Are you ready to kill?”

Nina Simone in 1969, the year she played at the third and final Harlem Cultural Festival. "File:Nina Simone -1969.jpg" by Gerrit de Bruin is licensed with CC BY 4.0.

In lighter moments, audiences witnessed the crowning of that year’s Miss Harlem, a young woman named Carolyn Byrd, and were treated to routines by beloved comedians Moms Mabley and Pigmeat Markham. Attendees could buy food, drinks, clothing and jewelry from scores of local vendors. “One woman came over and picked me right up,” Lawrence told the New York Times. “She said she had sold enough stuff to take care of her bills and send the kids to school.”

No one present thought this would be the last Harlem Cultural Festival — not after this bravura third outing that seemed to uplift the neighborhood and the city. There were no reported incidents of violence or disturbance at any of the six dates. Tony Lawrence said he wanted to go even bigger the following year and was already working on booking the Temptations. He was also making plans to take the Harlem Cultural Festival on the road to other towns. However, rancor between Lawrence and various backers led to plans for a 1970 Harlem Cultural Festival falling apart, and along with it the will to produce future festivals in the neighborhood. Lawrence himself dropped out of public life in the ‘80s, and mysteriously fell off the map altogether. As of last year, Rolling Stone was unable to confirm where Lawrence was, or even if he was alive or dead.

One might have thought that the discontinuation of the festival after that summer might have helped cement the 1969 festival’s place in history. Instead it just served to erase it, reversing the impact it had had. It was as if the Harlem Cultural Festival had never happened. It disappeared from the collective memory as those who were there passed away.

-----

On a hot August 17, 2019, my girlfriend and I made the long subway journey from Bushwick in Brooklyn to Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem. (Mount Morris Park had been renamed after Marcus Garvey in 1977.) This was back in the days when we took the subway and went places — back when New York City was actually a city to us, as deep and wide as one’s imagination could ponder, and not a finite collection of about 20 blocks that the coronavirus pandemic has turned it into. Our Black Woodstock trip was back when we could get vital input from neighborhoods and boroughs other than our own. All we needed to get this input was patience for an expensive and unreliable transit system, not the mask and life-and-death risk tolerance one needs today.

As we journeyed northward underground, I hoped the show would be as entertaining as it was sure to be culturally significant. My doubts were fueled by my own ignorance of the names slated to perform. With the exception of Talib Kweli and Freddie Stone (the guitarist and co-lead vocalist from Sly and the Family Stone), I hadn’t heard of anybody on the bill. As good as I considered myself to be at taking in new music, I now found myself falling back on my baser concertgoer instincts — I wanted to sing along to songs I knew. The advertised lineup today included musicians named Keyon Harrold, Igmar Thomas, Alice Smith and Georgia Anne Muldrow. “Who were these people?” I thought. “Where was, like, Jay-Z?”

Fortunately, we found ourselves seats with a good view of the stage in Garvey Park’s Richard Rodgers amphitheater. Had we arrived a little later, we might not have been able to see the stage at all, and may have been relegated to a patch of grass on the other side of a fence, such was the crowd.

The 50th anniversary of Black Woodstock only had a few hours to shine, rather than the six weeks allotted to the original. The city parks department was still involved, but instead of Maxwell House underwriting it, it was now Capital One. And though it was true that the star power that day was nowhere near the relative magnitude supplied by the original Harlem Cultural Festival, the emotional intensity of 1969 was in effect throughout. And indeed I was given many opportunities to sing along to songs I knew, while learning to appreciate artists I didn’t.

The concert was produced by the live event group Future X Sounds, an organization whose stated goal is to “shift the spotlight” to issue-driven artists and spark justice-minded conversation through music. Its producers, among them festival curator Neal Ludevig, sought to book African-American artists whose work demonstrated a commitment to activism. Bridges from past to present were evident throughout. Photographs taken at all three original Harlem Cultural Festivals were projected onto a screen onstage over the course of the evening, many of which had never been viewed by the public. There was an electric sense of “Wow. It all happened right here.” Ludevig drove this point home during his welcome address, when he listed off the stars of 1969 who had appeared “on this very stage.” I’ll admit I judged him a bit harshly for saying this, because it wasn’t technically true. The state-of-the-art bandshell we were gathered in front of was first unveiled in 2011. It was not the same stage that had been hastily assembled for the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival. That stage faced in the opposite direction of the present-day one. Hal Tulchin had requested a west-facing platform in 1969 so he could film with natural light as long as possible.

In the opening moments of the concert, jazz trumpeter Keyon Harrold introduced a piece he called “M.B. Lament,” a composition dedicated to Michael Brown, the unarmed Ferguson, Missouri, teenager who’d been fatally shot by a police officer in 2014. Brown’s killing sparked massive protests around the country and spurred the growth of the Black Lives Matter movement. Harrold, a native of Ferguson, eventually transitioned out of this original work into an elegant, languid rendition of George and Ira Gershwin’s “Summertime.” His unbroken segue from “M.B. Lament” into the “Porgy & Bess” standby prompted me to wonder if he wasn't intentionally drawing a connection between summertime and the untimely deaths of people of color at the hands of police.

Most of the featured artists dedicated at least one song to a performer who had played at the Harlem Cultural Festival 50 years before. Following his Ferguson-inspired medley, Harrold lifted the mood by launching into the 1968 hit “Grazing in the Grass” by Hugh Masekela. Harrold voiced his love for the late South African trumpeter and activist who had performed at the festival in 1969.

For her tribute piece, golden-throated singer-songwriter Alice Smith performed an octave-jumping rendition of Gladys Knight and the Pips’ 1974 ballad “Best Thing that Ever Happened to Me.” Hammond organ virtuoso Cory Henry, a gospel-rooted singer with cred in both the jazz and pop worlds, brought the house down with his full-blast performance of Stevie Wonder’s “Higher Ground.” From the moment the song’s unmistakable organ intro started, joy erupted in the stands. Henry’s powerful vocal delivery of the 1973 classic brought a renewed sense of urgency to the song’s narrative of personal spiritual redemption in the face of worldwide injustice — a message perhaps lost to over 45 years of steady radio and coffee-shop play. Henry’s full-throated tenor was akin to Wonder’s — and the sheer volume of the performance left me wondering how we survive without songs, and moments, like these.

From start to finish, the show was anchored by a jazz-rooted backing band led by the trumpet player Igmar Thomas. With few breaks, this six-piece group of virtuosic musicians, aided by two backup vocalists, accompanied every act on the bill, a lineup of seven artists stretching over two hours. Among the band’s horn section was a young, masterful alto saxophonist named Braxton Cook, who performed a solo piece titled “Trayvon Martin.”

With a genre-shifting style that was hard to classify, L.A.-based singer-songwriter Georgia Anne Muldrow brought an emotional intensity and improvisational skill that reminded me immediately of Nina Simone — an impression soon validated by her dynamic rendition of Simone’s “Wild is the Wind.” During the performance of her own song “Ciao,” Muldrow lamented an America in which police are still targeting and killing unarmed Black people, and expressed an urgent need to leave for Africa to experience a respite from this country’s demoralizing racial violence. (I later learned that these lyrics were created for this performance — the studio version of the song does not touch on these painful sentiments.) Muldrow shared part of her set with Keyon Harrold, with whom she had co-written a song. They and the band played beautifully off of each other, bringing an intense physicality to the performance that went beyond the words and music.

In his short two-song set, Talib Kweli, the evening's only hip-hop artist, reminded me of the sonic miracle that rap can be — at its pinnacle, the ultimate realization of rhythm, melody and ideas, involving the audience, the place and the moment. Using no recorded backing, the rapper kicked off his set with his 2004 song “Lonely People,” a lyrically dense masterpiece that heavily samples the Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby.” (The song has never been officially released due to a lack of clearance from Paul McCartney.) Kweli encouraged the audience to sing the famous McCartney-penned chorus that still cuts to the heart of the human condition — “All the lonely people. Where do they all come from?” — while in-between describing his take on fame in the hip-hop world, where nightlife often centers around the club, and success seems to hang on invitations to VIP areas:

Accomplished hip-hop lyricist Talib Kweli (right) was the headlining act at the 2019 “Black Woodstock 50th Anniversary” concert at Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem. ("Talib Kweli Greene" by Mike J Maguire is licensed under CC BY 2.0)